A new analysis says Vermont is not on track to meet its 2025 target for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, with declines in thermal fossil fuel use driven mostly — though not entirely — by warming winters.

The study, released last month by the Vermont nonprofit Energy Action Network, also shows signs of progress: Though rising temperatures are still the main driver of lower heating fuel sales, weatherization and electric heat pump adoption are starting to have a greater impact.

“Vermont’s efforts… are, ironically, being aided by the very global heating that we are working to do our part to help minimize,” the study says. “Relying on warmer winters to reduce emissions from fossil heating fuel use is not a sustainable strategy. … What [the warming trend] means for temperatures — and therefore fuel use — in any given year is still subject to variation and unpredictability.”

Like most other New England states, Vermont relies heavily on heating oil and, to a lesser degree, propane and utility gas, to heat buildings. This makes the building sector a close second to transportation in terms of the biggest contributors to planet-warming emissions in Vermont and many of its neighbors.

Vermont’s statutory climate targets, adopted in 2020, aim to cut these emissions by 26% below 2005 levels by next year, with higher targets in the coming decades.

“It’s technically possible” that Vermont will meet its thermal emissions goal for next year, but “at this point, primarily dependent on how warm or cold the fall and early winter heating season is at the end of 2024,” EAN executive director Jared Duval said. The transportation sector would need to see a nearly unprecedented one-year decline.

On the whole, EAN says it’s “exceedingly unlikely” that Vermont will meet its 2025 goal.

Warmer winters ‘not the whole story’

EAN found that heat pump adoption and weatherization are not happening fast enough, and what’s more, the current trend sets Vermont up for a Pyrrhic victory at best: Rising temperatures in the upcoming heating season would have to be at least as pronounced as in last year’s record-warm winter in order to reduce fuel use enough to meet the 2025 target for the thermal sector.

Either way, warming alone won’t get Vermont to its 2030 target of a 40% drop in emissions over 1990 levels, Duval said. The state wants to end up at an 80% reduction by 2050.

“The only durable way to reduce emissions in line with our science-based commitments is to increase the scale and pace of non-fossil fuel heating solutions and transportation solutions,” he said.

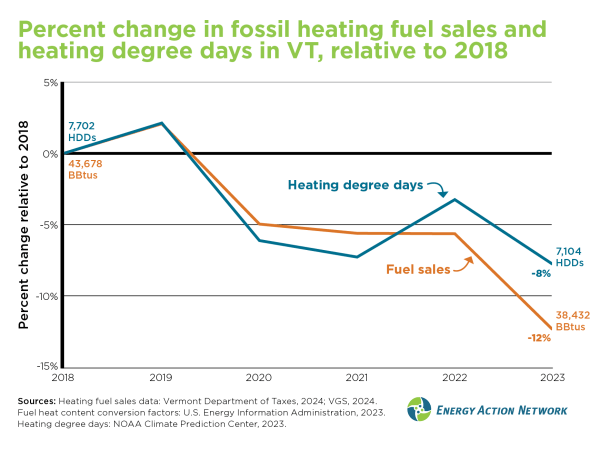

The EAN study found that fuel sales tend to decline alongside heating degree days: a measurement of days when it’s cold enough to kick on the heat. Vermont is seeing fewer of these days overall as temperatures warm.

“The reduction in fossil heating fuel sales as winters have been warming is not surprising,” Duval said. “Historically, fossil heating fuel use and therefore greenhouse gas emissions have largely tracked with heating demand, with warmer winters corresponding with less fossil fuel use and colder winters with more fossil fuel use. The good news is that’s not the whole story.”

In recent years, he said, fuel sales have begun to “decouple” from the warming trend to which they were once more closely linked. From 2018 to 2023, EAN found that Vermont fuel sales declined 12% while heating degree days only declined 8%.

“Fossil heating fuel sales are declining even more than you would expect just from warmer winters alone,” Duval said. “And that’s because many non-fossil fuel heating solutions are being adopted.”

Upgrades needed to accelerate progress

From 2018 to 2022, EAN found, Vermont saw a 34% increase in weatherization projects and more than 50,000 more cold-climate heat pumps installed in homes and businesses, with a 3.3% increase in the number of homes that said they use electricity as their primary heating fuel.

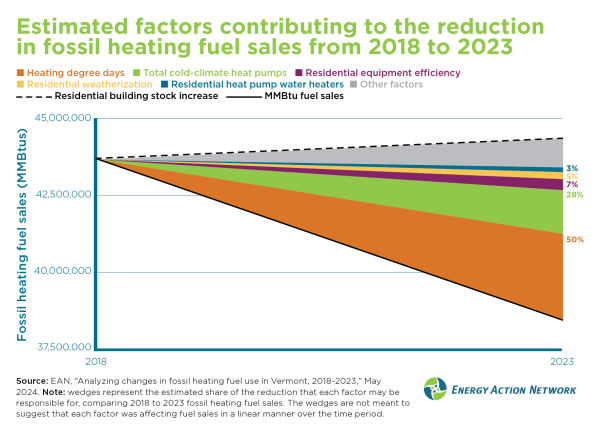

The upshot: The number of cold days explains 50% of Vermont’s declining fuel use from 2018 to 2023, while heat pump growth explains as much as 28% and other efficient upgrades explain a further 15%. The remaining 7% of the decline couldn’t easily be broken down and could partly be from people shifting to wood heat during periods of high fuel prices, Duval said.

“In order to achieve thermal sector emissions reduction targets without relying primarily on an abnormal amount of winter warming, significantly more displacement and/or replacement of fossil heating fuel… will be necessary,” the study says. Upgrades like heat pumps will lead to more sustainable emissions cuts, it says, “no matter what the weather-dependent heating needs in Vermont will be going forward.”

EAN is nonpartisan and doesn’t take policy positions, but research analyst Lena Stier said this data suggests that expanding Vermont’s energy workforce and tackling heat pumps and weatherization in tandem would spur faster progress on emissions cuts, while keeping costs low.

EAN based its estimates of fuel use and emissions impacts from heat pumps on the official assumptions of a state-approved technical manual, which Duval said may be overly optimistic. But Stier said the reality could differ.

“We’ve heard anecdotally that a lot of people who have installed heat pumps in their homes… are kind of primarily using them for cooling in the summer,” she said. “So our kind of assumption is that, in reality, it would be a smaller share of that (fossil fuel use) reduction coming from heat pumps.”

While fuel use declined overall in the study period, he said this came mostly from people using less heating oil specifically — propane sales actually increased in the same period.

Duval noted that propane is cheaper than oil on paper, but actually costs more to use because it generates heat less efficiently than oil does.

“Once you look at that, then heat pumps become that much more attractive,” he said.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated for clarity.